The costs of other pandemic measures mean that covid-19 vaccines will probably turn out to be a good buy, says John Appleby, and the full calculations will raise questions about NICE methods

Pfizer and BioNTech have announced the early results of their covid-19 vaccine trial,1 and immunisation for the novel coronavirus could be available in months. Of course hurdles remain, and more data need to be gathered about the efficacy and safety of the vaccines being trialled. One hurdle that new health technologies usually have to jump is cost effectiveness: is the value of the benefits worth the costs?

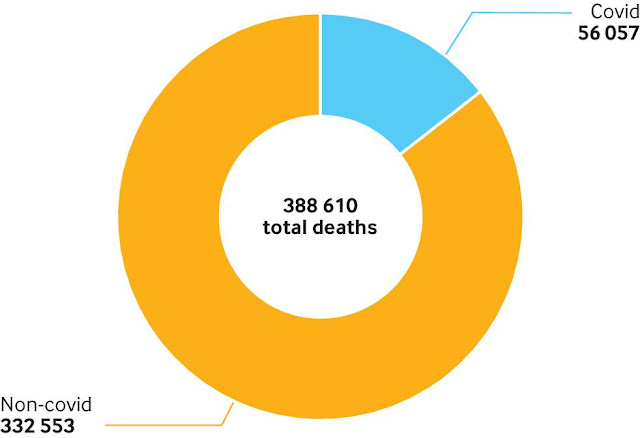

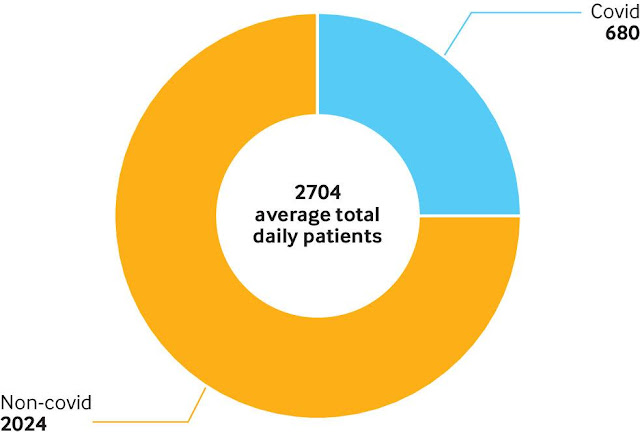

Although they have saved lives, the tactics used so far to try to get on top of the pandemic have had huge costs to people’s livelihoods and, as the NHS reprioritised its work, to people’s health (fig 1, fig 2). A rolling series of lockdowns and targeted isolation have been the only interventions available for restricting coronavirus transmission, but they are not the ultimate answer to tackling covid-19. It seems inconceivable that governments would dither over the value for money of an effective covid-19 vaccine.

On the other hand, the chancellor’s words cannot be taken literally; clearly there must be a limit to what the government, any government, would—or could—fund. Whether the first covid-19 vaccines are cost effective remains to be seen—there are too many unknowns to make a sensible, even rough, calculation at the moment.

Savings against existing pandemic measures

Given the deals done by governments, however, a covid-19 vaccine will probably be deemed a good buy—not least because of the savings in costs associated with current pandemic measures. The Office for Budget Responsibility, a public finance watchdog, estimates that the current measures to support individuals and the economy, as well as extra spending on the NHS and other public services,7 add around £193bn (€216bn; $256bn) to this year’s deficit (fig 4). Public sector net borrowing could total around £322bn (up from £57bn in 2019-20), net debt could be 104% of the UK’s gross domestic product, and tax receipts could be down by almost as much as is spent on the NHS in England.7 Add to these the probability that, in the words of the Office for Budget Responsibility’s Fiscal Sustainability Report in July, “the UK is on track to record the largest decline in annual [gross domestic product] for 300 years, with output falling by more than 10% in 2020.”

Cost of UK government coronavirus policies up to 20 July 20207

If the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) were given the task of assessing a covid-19 vaccine’s cost effectiveness, these wider economic losses and effects of spending would not directly feature in its calculations. This is because its perspective on costs and benefits is drawn fairly tightly around those falling on or accruing to the health and care services and the health benefits to patients and others.9 Nevertheless, NICE guidance on the approach to economic evaluation does recognise the fact that healthcare technologies might have wider benefits or costs and that these can be reported separately with prior agreement of the Department of Health and Social Care.

Covid-19 may be unusual (to say the least) but it draws attention to a debate for NICE (and its ongoing review of its assessment methods10) about the extent to which we want it to broaden its perspective. As the world has painfully learnt, health (and care) and our economic lives are (and always have been) inseparable.

No comments:

Post a Comment